From Transmetropolitian review by Barabule Cutarescu

Disclaimer: The entirety of this text is fiction and meant for entertainment purposes only.

I further request and command each and every one of you, at the cost of my friendship, to beware of bringing any but good news from the outside world, no matter where you roam, or what you may hear and see.

-Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron (Preface to the Ladies), 1353

The First Story

Hello? Hey, it’s me again, the Moldovan potato, Barabule Cutarescu, back on my anarchist commune in the hinterlands of Romania. I literally just got back, it’s only been a few weeks since my return, so I guess I better get busy telling you creeps about what the fuck just happened. It makes about as much sense as anything else I’ve ever written, at least in English, but along the way you might learn something about Ukraine, France, Italy, Russia, and of course Moldova, the shithole where I was born.

After the Russian army invaded Ukraine in the winter of 2022, a bunch of my friends were able to get out of the country in their shitty little car and made it all the way to my commune. None of them were men. All the men were stuck in Kharkov and we thought about them often, but only when we weren’t distracted by the impending harvest. While we watered corn and threshed wheat, endless bombs fell on Kharkov, even after the Russian army abandoned that front and withdrew to the glorious motherland. We all hated that our guy friends were stuck across the border, but week by week, as the war became even more bloody and insane, some of my Ukrainian friends began to get angry at us Moldovans when we said anything regarding their glorious motherland. We respected this sentiment, for a while, and if you couldn’t guess, I was the first to start feeling resentful.

My partner convinced me to leave before I exploded, that she could handle things, that I should just leave, go wander while I still could. The harvest was basically over, the days were still warm, so I said yes, I would go travel, with no other objective than to not be on my commune yelling at my Ukrainian friends about the role of western arms manufacturers. I could have blown up at them, of course, told them they were a bunch of zombies ignoring where Saint Javelin came from, but that would’ve been pointless, because all of them just want their loved ones back, and they viewed a Ukrainian military victory as the quickest way to see them again. I didn’t. I even offered to organize smuggling our friends across the border, like I already did once before, but none of them could stomach the risk, so I listened to my partner. I just packed my bags and left.

In my hurry to get the fuck out of there, I grabbed two random books for the trip, thinking they were something else. One was Viata lul Samuel Belet, or Vie de Samuel Belet, or The Life of Samuel Belet, a book by CF Ramuz, written in French by this famous Swiss author who used to be on the 200 franc bank note. I had the Romanian version of the book, published in 1987 by UNIVERS, a press which is still around, only back then they operated under the communist government of Nicolae Ceaușescu, who apparently found no objection to them publishing Viata lul Samuel Belet. And yes, once again, for the hundredth time, Romanian is a Latin language, not a Slavic one.

I got the book a few summers ago in Iași, the capitol of Moldova, the big city of our region. I bought it with the change in my pocket off this guy on the street peddling a sack of books. Having heard Ramuz was somehow connected to the old-school anarchists, I grabbed Samuel Belet, paid the guy, then drunkenly staggered back to my friend’s place. When I woke up, I had a new book, and back in the late-communism days of 1987, this book used to cost 14 lei, which today will maybe get you a few liters of petrol.

I thought about all of this after I got on the village bus at dawn and pulled the books out of my bag. I don’t know why I brought that book, or the other one, The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio, which I’d also never read. I thought the book was going to be in Italian, but when I opened it, everything was in this fucking English. Rocking there in the back of the rural bus, speeding towards Iași, with no clue where I was actually going, I decided right there that I’d go to Paris, just like the main character of Samuel Belet, and after that I’d go to Firenze, the main setting for The Decameron. If you don’t know what Firenze is, I’ll let you know right now that it’s Florence, as the British imperialists liked to call it, the very birthplace of this Renaissance which apparently people are still raving about.

I was happy with my sudden decision, this little vacation plan, and that’s when my journey ran into it’s first roadblock. After a sudden burst of talk over his radio, the bus driver pulled over and claimed five of us would have to get out, as he’d illegally packed too many of us in. There was a police checkpoint was up ahead. Having got on dead-last, I was off the bus the moment he opened his doors.

It is a mighty fine thing, noble ladies, to hit a fixed target, but it is almost miraculous when some unusual thing crops up suddenly, and is pierced directly by the archer.

-Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron (First Day, Seventh Story), 1353

The Second Story

Like I said, five of us had to get out of the bus, and luckily there wasn’t any rain. We waited there, smoking cigarettes (all of us), and the eldest looked like she was 60. Thanks to her, an empty VW sedan pulled over fairly quickly, only I was the odd person out, being the youngest. One of the guys offered to stay out there with me but I told him I was fine, that I’d hitchhiked these roads my whole life, which was true. Even if no one picked me up, a petty-capitalist bus driver with an empty seat would eventually be along, assuming I could hoof it to the next village, which was about an hours walk.

I’d been so subsumed in my village life, going crazy around all the talk of Ukraine, that I barely walked anywhere, at most to the river or the local bar. Now I was strolling in the sun through beautiful Moldova, and it is truly beautiful, all rolling hills and picturesque little houses, and being in a really good mood, I lit a big spliff. There weren’t many cars, all of them were heading the wrong direction, but eventually I heard a loud engine approaching from behind, so I stuck out my thumb and was surprised when a tricked-out BMW screeched to a halt in front of me. In all the excitement, I somehow lost my spliff, but I was already high enough to be a bit paranoid while I inspected this good samaritan.

His car was immaculate, nothing in it. He beckoned for me to hurry, he looked clean-cut, with a fancy, shiny watch, so I quickly threw my bag in the backseat and joined him up front. I had time to thank him before we’d accelerated past 100 kph. He told me he always drove fast, and as if he’d planned it, a staticky voice broke through his speakers, prompting him to pick up a radio receiver. For a moment I thought he was a cop, but as I listened, I realized these were drivers sharing real-time information on police speed-traps. We decelerated from our near 200 kph as we drove through one long valley with a gas station, and just as the radio described, a cop was parked there stuffing his face with KFC.

Once we were out of the valley, the guy sped off and immediately got back on the radio, asking about conditions ahead. This went on all the way to Iași, and I was truly on the edge of my seat the whole time, especially when he swerved between cars and slow-moving căruţă (ie: fucking peasant horse-wagons on the highway). We survived, and soon I was gliding beneath the Amazon tower into neo-liberal Iași, a hell-hole I truly love, having spent my youth here. I asked my insane driver if he wanted to grab a drink but of course he said no, though he did look me up and down first. In case you didn’t guess, this guy was a fucking gangster who most likely grew up in a village just like mine, and once I grabbed my bag and shut the door, he was off like lightning to do who knows what, leaving me to hoof it up to my friend’s apartment for a big surprise.

First I bought a bunch of groceries from this wild little Soviet-era market, an insane, concrete brutalist nightmare that just devours your consciousness as you walk in, leaving you puzzled as to exactly where you are. Underground? In another building? Upstairs? Another dimension? Despite the confusion, inside is an organic farmers market where you have to bargain for everything. It’s where I used to get my groceries, and with two bags in hand, I hoofed it up the hill and pressed all the buttons at the intercom to my friend’s apartment building. Eventually someone buzzed me in and climbed up five flights and then banged real loud. My friend was sleeping, she wasn’t happy, but when I showed her all the groceries and promised breakfast, she immediately went back to sleep, leaving me to settle down, make coffee, have a second spliff, and wait for her to wake-up. In the hours before that happened, I started to read my copy of Viata lul Samuel Belet.

The first chapters struck me pretty hard, being centered on a protagonist eager to leave his little Swiss village, located in the same Jura mountains where those French speaking anarchist watch-makers were spreading anarchism and living anarchy. Samuel knows nothing else aside from his tiny mountain village, but as he ages, it becomes clear he will never grow there, not even after he rises from farm-hand to clerk for a local capitalist. After his doomed cis romance implodes, Samuel wanders from village to village as an itinerant farm-hand, all during the late 1850s and into the 1860s. This is about as far as I got before my friend finally got up from her coma.

She works at a famous bar in Iași and usually gets home either just before or just after dawn, so it was after noon when I poured her some espresso and started cooking breakfast. She caught me up on all the Iași news, how most everything was still dumb, the same neo-liberal hispters were still taking over, all our favorite places sucked shit, and soon it would be cold again, making Iași even more miserable. We ate our healthy, organic meal in relative calm until I mentioned I was on my way to Paris, which made my friend excited. All amped up on coffee, she proceeded to buy my plane ticket on her credit card, citing the need for some pocket cash when really she wanted to live vicariously through me, being tied to the bar she still co-owned with her ex-boyfriend, who used to be an anarchist but was now mostly a petty-capitalist shit-head.

My friend got me a cheap ticket on Wizz Air, which might sound fake but is a staple among Euro-trash scum-fucks like me. It’s one of those brave airlines that actually fly into Iași, enabling us barbarians to travel across the EU, of which Romania is allegedly a member. My flight was the next evening, and even though it was cheap, I handed my friend a couple hundred lei, given that one euro is worth about five lei. By the way, the only reason Romania still has its own currency is precisely because it is worth less than the euro, enabling a lot of Western-European and US companies to set up shop and exploit us ignorant peons not quick enough to see the royal scam. Anyway, all this to say my one-way ticket to Paris cost about €50, and it was even leaving the next day. To celebrate my imminent departure, I decided to accompany my friend to the bar that night with her promise of free, unlimited drinks.

After cooking an early dinner, we walked down to the street-car, one of the old Soviet kind that seem like they’re from 1916. I’m exaggerating, maybe, but some of them have heaters now, meaning people don’t have to freeze their asses off anymore. We got on without paying, a time-honored tradition, and then hoofed it over to the back entrance of this bar I can’t describe to you, but it’s really popular. Only a few bums were inside chopping onions and re-sweeping the floor, part of the usual crowd, but I could barely hear anything because in the back room, behind black drapes and a red barrier rope, was the very VIP club room, controlled by her ex-boyfriend. This was his domain, and lately it had gotten more popular thanks to some IG freaks and other alt-right influencers like Andrew Taint and his brother Tristan, who vouched that Iași was very VIP and civilized. I didn’t go back there, I helped my friend get the bar ready, doing my best to ignore the famous DJs and their lackeys heading in and out of this VIP grotto. They all pissed me off, just like my friend’s ex, who was clearly letting any internet scum into his den.

Soon it was opening time. The kitchen served only bacon-wrapped hot-dogs with grilled onions and all the condiments, even outlandish hot-sauces from distant places that are almost bio-weapons. During the first hours, the bar filled with young university kids, some neo-liberal hipsters, and no one I recognized from the old days. I stayed behind the bar that night, pouring drinks and actually talking with the customers, which is something my friend is famous for never doing. However, once I’d talked to a few people, I instantly understood why it was best to keep my mouth shut and ignore everyone.

Don’t ask me why, but that night the topic on everyone’s Romanian tongue was the city of Kherson. It was about to be reclaimed by the Ukrainians, or liberated, as everyone kept saying. All that October, my Ukrainian friends worked themselves into a near-patriotic fervor as the Ukrainian army fought its way closer to Kherson, claiming kilometers of ground every day. For my friends, living in exile on my Moldovan commune, it was a glimmer of hope that the war might be over soon, and their fervor to believe this drove me to flee before I ruined some good, solid friendships. You can imagine how horrified I was when every baby-faced student and mealy-mouthed techie entrepreneur was prattling on about how the war was going to be over soon, that the historic victory was just around the corner, that their great neo-liberal Europe would keep expanding. Rather than scream at these people that they were fucking idiots, I threw in my rag and retreated into the VIP section, even though I was dressed like shit, blowing past the bouncers like the scum-fuck royalty I was.

My friend’s ex was behind the DJ, bobbing his head with all the other cronies, and I circled the floor with my drink looking at all the private booths filled with very interesting women and men who were likely gangsters. Imagine my surprise when one of the booths held my patron of the morning, the speed-racer peasant-bro who picked me up hitch-hiking, only now his arms were around two women with fake breasts and angry eyes. He didn’t recognize me, and I went back to the apartment soon after, disgusted with my home-city of Iași, the place I love to run away from.

Monkish folks are a foolish, strange, peculiar set, they think themselves better and wiser than everyone else in everything, when, as a matter of fact, they’re worse than the rest of us, and not being spunky enough to stand on their own feet, they find refuge, like pigs, where they can stuff themselves.

-Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron (Third Day, Third Story), 1353

The Third Story

I was asleep when my friend got home, just as she was asleep when I woke up. After making coffee and eating some breakfast, I settled into her cozy sofa for another long read of Viata lul Samuel Belet. The further I got, the more Samuel Belet’s story mirrored my own, having exhausted every avenue offered in his rural Vaud region of Switzerland where everyone speaks French. The guy eventually makes his way across the border to the Savoie region of France where he blends in with the other peasants who work the same shitty jobs as him. Eventually he meets an anarchist, and with this anarchist he travels to Paris, the city I was going to fly into later that night.

Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz published Vie de Samuel Belet in 1913, shortly before the outbreak of WWI. Just like Samuel Belet, young Ramuz left rural Switzerland for the tumult of radical Paris and stayed until that horrible war descended across Europe. He must have known something terrible was coming, because he has Samuel arrive in Paris only a few years before the fateful Siege of Paris in 1870 and the great Commune of 1871 that followed. The Paris he depicts in Vie de Samuel Belet is one that’s about to be erased by war, civil or otherwise, and I only just started the Paris section when my friend woke up, desperate for coffee and eager for silence, so naturally I talked her ear off.

I ranted about how insufferable the hipsters were in her bar, staking all their hopes and dreams on the liberation of Kherson, alleged to be underway as we spoke. My friend just told me to shut up, that in all honesty, she didn’t care about the hipsters or Kherson. In fact, she didn’t care about anything other than making enough money to retire, something which would have already happened if first COVID and then the war hadn’t fucked everything up. She’d already wasted enough of her life on this bar, with her fucking ex, and her only true hope was that she’d be able to cash out before the war came any closer to Moldova. With any luck, she’d be in Mexico within a year, so she didn’t care what the hipsters said or believed or thought. After she left, she wouldn’t care if a bomb fell on the bar.

With her now diamond-pure nihilism made clear, I cooked her breakfast and changed the subject to our shared passion of hiking. Being a pure concrete Soviet city-girl, she always liked hiking more than I did, and even though I always talked like a coked-out marionette during our treks, my friend appreciated my knowledge of Moldovan plants and trees, something I was born with and took for granted as a backwoods-ass peasant. While we ate breakfast, we planned a hike from Iași to my commune, one that would start at the edge of the city and wind through the farmland and hills, taking us nearly half a day. Usually we’d drive out somewhere to go hike, often hours away, but this future hike would reveal the transition out of our Soviet city into the rolling countryside.

In case you were dying to know, horse-drawn wagons are banned in Iași, given you can’t have a căruţă clattering in front of the Amazon tower, but at the edge of the city this prohibition begins to blur until you eventually see wagons on the highway itself. To my friend and I, these căruţă are a symbol of unconquered Moldova, a mode of transport that doesn’t rely on a global economy, petroleum, or any specialized facility other than an iron-smith. Aside from some hay for the horses or mules, it’s all but free and pays for itself a thousand times over, turning a half-day hike into just over four hours, not that many peasants ever travel that far in a căruţă.

Later that night, my friend drove me to the airport early enough for us to take a farm-road behind the landing strips and smoke a giant spliff under the roaring planes. Surely enough, while we sat there on the tailboard of her truck, a căruţă went rocking past, it’s rear lit up with two red flash-lights taped to the sides. That’s how close the peasants are to Iași, and after getting really high out there in the fields, this image of a căruţă fading into darkness lingered even as I kissed my friend goodbye and got in line for the airport security. I was really high, so I just sort of floated in with a smile, and all I could really see was that fucking căruţă with the cheap flashlights. It was in my brain when I finally took my seat on the plane, and I’m pretty sure I dreamed about it all the way to Paris. I don’t remember any of my flight, just the căruţă heading down the dark farm road behind the modern airport.

In a daze, I made it safely into the nation-state of France and took a shuttle bus into the center of Paris, where another of my close friends lives, although some might call her my ex-partner, or something. It doesn’t fucking matter though, does it, but needless to say, I hadn’t alerted her to my arrival, so when I got to her building, I was forced to press all the buttons on the intercom. Unlike in Iași, I found no stranger willing to buzz me in or even admit to knowing my friend, their neighbor of many decades, so by process of elimination I singled out the button for her apartment, which I then pressed for roughly five minutes. While it took me longer than expected, I realized she was probably dead asleep, it being around 7 in the morning, so I waited until someone came out and forced my way inside, assuring them my friend was asleep and that I’d just arrived from Marseilles, hopefully accounting for my bizarre French accent. With this accomplished, I then banged on my friend’s door until I heard a faint noise and then a series of clicks. She wasn’t mad I was there, just amazed, and I recieved a big kiss once she opened the door.

Thing about my friends is that she comes from a really old, really wealthy Parisian family. She’s joked about being descended from the indigenous Celts who were here long before the Romans, the ones who made an alliance with the gnostic followers of Mary Magdalene & Co., but that’s more than likely a complete fabrication, of both hers and mine. In reality, her family survived the Great French Revolution but had to flee their family apartment, this apartment, some time in April of 1871, right before all the brave fighters of the Paris Commune were cut down or thrown in dungeons. Then they came back. Some might call her family liberal fence-sitters, or something of the sort, but she freely admits they’ve always been part of the ancienne bourgeoisie, meaning their wealth is fucking ancient.

Anyway, I don’t know what’s wrong with my friend, but as usual, she began making me breakfast, mothering me. Behind her robe-shrouded form, through some giant fucking windows, was a view of the piece-of-shit Eiffel Tower, a view she’d known all her life, this being her literal family apartment. What kind of world do we live in where a Moldovan potato like me can fly in on a jet-plane to the City of Light and get cooked breakfast before 8 in the morning? I guess this is supposed to be what all the ecocide and greed is for, these luxuries like 50 euro Wizz Air tickets from Romania to France, and apparently if Russia isn’t defeated, scumbags like me won’t ever get to have a vacation in gay Paris. But as it was, democracy and freedom still prevailed in the European Union, and your faithful Barabule was able to fly across the continent while the Ukrainian army crept ever closer to Kherson city, believing the end of the war was surely at hand.

There’s no lack of examples in our city, to illustrate every point, as there is no lack of anything else, and yet I think we should go a little beyond it, like Elisa, and tell of things that have taken place in the outside world.

-Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron (Third Day, Sixth Story), 1353

The Fourth Story

After breakfast, my friend asked if I wanted to use her regal, claw-footed bathtub, a favorite of mine. My truly natural inclination would have been to not even say yes, but just to run back there. In an effort to be less overtly selfish, I settled for a shower and went out with her to our favorite Parisian street spot, where we eventually ran into some familiar Parisian street freaks from the old days and soon enough we were on the river smoking spliffs under a warm autumn sun. By the afternoon I was pretty worn out, tired, so my friend and I went back to her apartment and sprawled out on her giant sofa to watch her favorite, the French cable news, through which she rapidly cycled, something I always left in her hands. It’s the pre-social media form of scrolling, by the way, a method to avoid hypnotism and render the viewpoints as meaningless as they are. Now everything’s already meaningless, a priori, and you can just scroll right through. It’s even designed that way.

A lot of the French news was salivating over the impending liberation of Kherson, but my friend and I agreed it wouldn’t signify a swift end to the war. If anything, it was some sort of strategic trap, a lethal quagmire being presented as a gift, but what did we know, being privileged westerners behind the front lines. The media was drumming up support for this alleged milestone in the liberation of Ukraine, an endless chorus of cheer-leading with little substance beneath. In between this, we watched garbage, trash, and eventually we passed out, and when I woke up my friend had made us dinner. It was the final weeks of October, 2022, and I was really far away from Moldova.

I did take my bath that night, and I stayed in it so long I was able to finish Vie de Samuel Belet. Long story short, Samuel leaves Paris right before the Prussians encircle it and returns back to his French speaking region of Switzerland, the Vaud, and he eventually settles down into a peaceful, simple, rural, peasant existence. I tossed the book aside, not because it wasn’t good, it was, but because I related so much to the main character, who in the end just goes home to his peasant hut, just like Ramuz, just like me, again and again. So finishing this book in a Parisian bathtub only made me feel lost, like I’d made a stupid, impulsive decision and run away from the same peasant hut I’d inevitably be running back to. This feeling only got worse when I got out of the bathtub and watched the news with my friend, filled to the bring with insane propaganda, some of which encouraged French citizens to conserve energy in solidarity with Ukraine. This is the shit I was watching when I fell asleep in a well-heated Parisian apartment thousands of kilometers from the front lines.

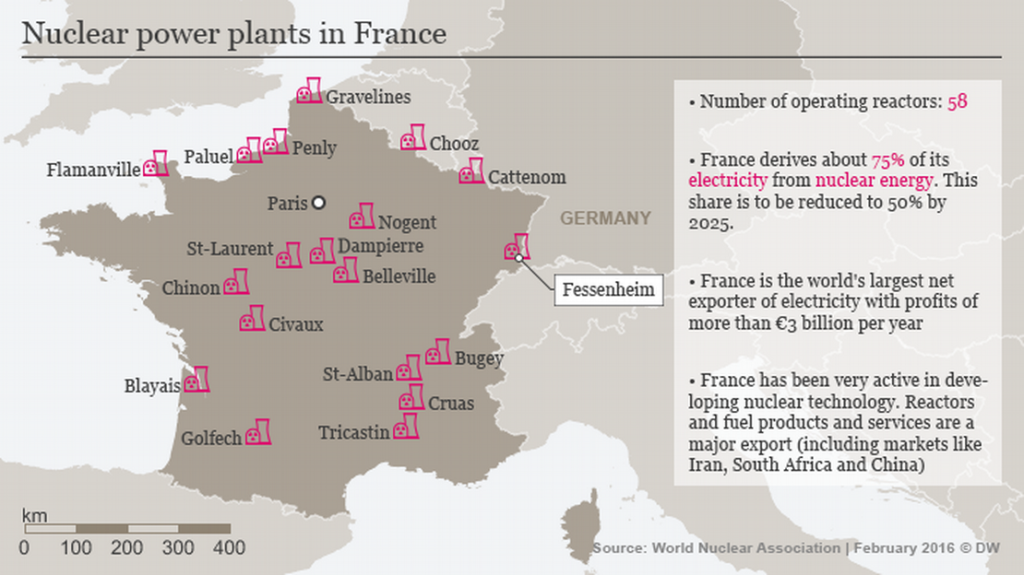

I stayed some days in Paris, living a simple, boring life. Every morning my friend and I went to the same corner spot where we sat at a table on the street and drank what we wanted and ordered what we wanted and used the bathroom and smoked cigarettes and lingered for hours, often running into old friends. Many of these weirdos were anarchists, and all of them were talking about Alfredo Cospito and his hunger strike against solitary confinement in a Sardinian prison, treatment generally reserved for the same mafia-types that often have immense influence in Italian politics and business. My friend and I had much respect for Alfredo, given he is literally the only human to react to the nuclear disaster at Fukushima, knee-capping a door-to-door salesman of nuclear reactors and then writing about it with his friend. Alfredo was not exactly a beloved figure of the Italian state, and the French state had reason to be wary also, given they have nuclear plants every two kilometers out in the countryside.

I was happy this handful of Parisian anarchists were talking about Alfredo and his hunger strike, given they could be talking about the liberation of Kherson, but in the end, we were all just a bunch of decadent westerners blowing hot-air at the cafe. To be real, Alfredo began his hunger strike just two days before, and it really was impressive to hear some French losers talk about it. He was really going to do it, it was urgent, and starving himself clearly beat a slow death in an isolation cell. I thought about Alfredo a lot those days in Paris, especially because I was enjoying a type of aimless freedom he is now unable to experience.

The local anarchists weren’t just talking about Alfredo, they were talking about the end of the strict COVID lock-down measures and how any day now the streets of Paris would erupt with riots, the same kind that were happening every week before the lock-down. It was taking many months for people to thaw out, there were already people preparing to block a big-agra hydro-compound near a village south of Poitiers, and in the Parisian suburbs, the banlieue, people had been fighting the cops the whole time, lock-down or not. Everyone agreed, it was all about to pop, again, and I have to say, it was exciting.

My friend and I are the kind of Gen-X Euro-trash scum-fuck anarchists who barely exist these days, but we exist. We lived through the collapse of global communism and sludged through the delirious rise of global neo-liberalism, a time which neutralized many of our peers, but not all of them. Just like us, Alfredo Cospito is a bona fide Gen-X Euro-anarchist, but unlike most of our generation, he fought tooth and nail against this system of death, and for this crime he was in solitary confinement in a mafia prison on the Italian island-colony of Sardinia. While my friend and I spent our days in idle Parisian tranquility, lazily chatting about his situation at the cafe, Alfredo was literally starving himself.

While we ate our lazy lunches, I tried to remind these French anarchists what a truly potent moment that was, way back in 2012 when Alfredo shot that guy in the knees. I was in Oakland, rioting with a bunch of demented losers, and it was May 1, 2012. Suddenly, someone in the crowd announced that riots in the city of Seattle had grown so intense that a state of emergency had been declared. At this announcement, everyone in the riotous mob cheered, and it was one of those brief moments in this life where it felt, again, like we were winning.

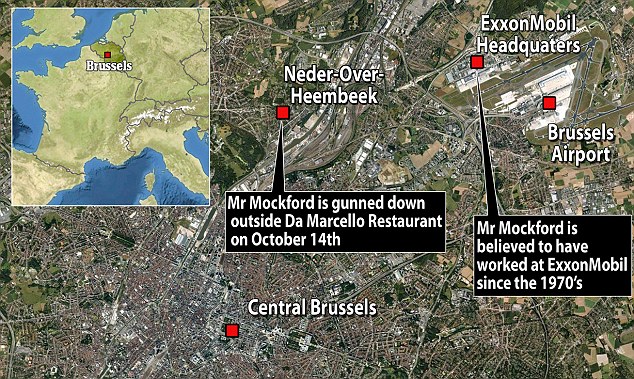

It got even crazier a week later, on May 7, when Alfredo Cospito knee-capped Roberto Adinolfi, head of an Italian nuclear power behemoth. It was definitely anarchy time, as they say, and despite a fuck-ton of repression, including the arrest of Alfredo and his accomplice Nicola, some people managed to gun down an Exxon executive in front of his wife near the outskirts of Brussels. That’s in Belgium, by the way, HQ of the EU, and these assassins were never caught, just as the act was never claimed. This happened exactly a month after Alfredo and Nicola were arrested, and while there is no connection between the events, it was surely heavy times, and I discussed this with the Parisian anarchists at my friend’s favorite restaurant.

In the evenings, when my friend had passed out in front of her TV, I walked myself to the river (ie: the Seine) and hung out with all the immigrants, some from the Dominican Republic, others from West Africa, and all we did was smoke hash, drink, and listen to music. There were a bunch of people sleeping in tents on the river and the guys kept talking about how there were no evictions in the winter, which meant people could camp on prime real-estate, no cost. I never stayed too late, leaving the homeless guys at the chilly riverfront to go back to my old friend’s over-heated apartment. I’d stay up getting high, watching the huge screen filled with all the Euro news stations, reminding me to save energy, to turn off the lights for Ukraine, to prepare for the hardest winter we’ve ever known.

Winter was in fact coming, I could feel it this far north in Paris, so I decided to leave near the end of October and go visit my other old friend in Firenze, the city where her mother was born. I said goodbye to Paris and all my friends, got on the regional south-bound slow-train, and continued my aimless journey towards the French Riviera. I could have been back in Moldova, yelling at my Ukrainian friends that nothing would change after the Russian army abandoned Kherson, that the tide wasn’t going to turn before winter, that something extremely bad was approaching. Only a monster like me would take away their hope of a full Russian retreat, so there I was, clattering out of the Gare de Lyon, on my way to Italy with a book called The Decameron in my lap. This is when the tale here gets a little bit strange.

I’m going to tell you the following story. Though the subject of it, loving ladies, is in spots not quite proper, I shall tell it to you anyway, that it may amuse you. As for you who listen to it, do as you would on entering a garden, when you stretch out your dainty hands to pluck the roses, but leave the thorns behind.

-Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron (Fifth Day, Tenth Story), 1353

The Fifth Story

On my train heading south through France, I read a very un-French book, The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio. I’d had it on my shelf for years, decades even. If my memory is at all reliable, I found the book in the discount box of a junk store in London. It cost me fifty pence and its blue cloth cover was smeared with what looked like drops of concrete water, as if some worker had briefly handled it while demolishing a house. I must have never opened it all those years, because I expected the text to be in Italian, and this is how I ended up refreshing my English on the train ride south from Paris.

I knew nothing about The Decameron, except for maybe having the vague idea it was the Don Quixote of Italy. It’s not only over 200 years older than Don Quixote, it’s the alleged genesis of western literature, which is odd, given that The Decameron borrows its structure from The Thousand and One Nights, even incorporating one of its stories, the funny one about a man being tricked into thinking he’s pregnant. Before I get ahead of myself, I’ll just remind you that The Thousand and One Nights is the giant compendium of tales narrated by Scheherazade, the virgin who must tell a story each night or be killed by a psychopathic Persian king. This is the book where Aladdin comes from, so I’m sorry if your brain-dead totalitarian culture convinced you it was created at Disneyland. In truth, it comes from the mouth of Scheherazade, and her 1001 stories within a story inspired Giovanni Boccaccio to write The Decameron as 100 stories within a story.

By all accounts, Boccaccio returned to Firenze in 1349, shortly after his step-mother and father died during the Black Plague, a pandemic which killed 75% of the city’s population. He started writing a collection of stories framed within this horrible moment, with the intro providing a quick introduction to the plague in Firenze. Boccaccio then describes seven women meeting in a church, Santa Maria Novella. Everyone is dead, all the houses and palaces are deserted, everyone is talking about death, the dead are everywhere, and as one of the women declares, I think it would be a mighty good thing if we all left this town, that through stubbornness or nonchalance we may not fall into a mess we could avoid if we cared. These seven women then recruit three kind men to accompany them up the hill to an empty palace near the village of Fiesole, which overlooks the red-tiled roofs of Firenze, or Florence, as British imperialists like to call it, providing much confusion to hapless readers.

I read this book deeply on that train ride to Italy, amazed that it was set during an ancient pandemic. As I learned, the characters retreat to their hilltop refuge and decide that each of them will be ruler for a day, wearing a crown of laurel (or bay-leaf) to signify their reign. As their supreme privilege, these rulers-for-a-day could pick the topic of the stories which they would tell to pass the time, the only condition being that these stories couldn’t involve the plague, of which they’d all heard enough. I suppose this was the pandemic novel everyone had been talking about writing, only it was written in the 1300s and could never be topped, apparently, because I was laughing my ass off all the way to Nice. This shit is really funny, like legit, laugh out loud, LOL type of funny. It rips the shit out of the Church and its priests, a bunch of lechers, pedophiles, and charlatans according to Boccaccio. It reveals a Mediterranean world, a post-Roman world that extends all the way to the isle of Britannia and even to India, and while it is filled with greed, violence, money, and terror, it is surprisingly free of racism.

As I plunged through the racist, conservative hotbed of southern France, I read story after story of Turks and Berbers, Arabs and Albanians, all of them treated equally, bouncing back and forth across the sea in their misadventures. Not only are there women protagonists of this story, they posses agency and make their own choices, with motivations often as base as the men. I had no idea such an encyclopedia of that ancient world existed, and while Boccaccio definitely borrowed the structure of The Thousand and One Nights, he filled it with stories of the insane Mediterranean, with historical figures like Gioto appearing alongside historical Florentine families, who are often brutally mocked as being ugly people, or worse. Rival cities are blatantly insulted, especially Pisa, but none is more savaged than the Vatican itself, while Rome gets off with being called a simple shithole, the lowest city on earth that was one once the highest.

I passed out somewhere along the Rhône River and woke up at my first stop, Nice, a word with a fate reserved for select few. There were no more trains, it was late, I had to sleep in the station, but at least I had my Boccaccio to help me. Around dawn, I boarded a train east towards the Italian border, a coastal town called Ventimiglia, the end of the French line. From here, I got on TrenItalia, the Italian line. Real proprietary, these nation-states of the EU. I took my time on this gorgeous coastline, savoring the view and putting down my Boccaccio to just stare out the window at the bright and glistening Ligurian Sea. I stared like this all the way to Genova, then I got off and smoked a spliff by the sea, given it was warm.

There were bunch of guys around, a lot of them immigrants, basically doing the same thing I was, and I talked with a few until all of them suddenly disappeared, all but one, who lingered long enough to tell me a cop was staring at me. Being an idiot, I turned around and saw this really obvious plainclothes guy smoking a cigarette and watching me, just me. Not having an ounce of sense, I immediately ran across the street, an act which made the guy start walking away. I didn’t really want to follow him or make much of a scene, but I did scream que cosa over and over until he disappeared around the corner. Then I realized I had a burning spliff in my hand, so I took a drag, and then I heard all the guys in track-suits start laughing, because who the fuck was I anyway?

They came back around me after a while, talking a bunch of shit, but I just sat there smoking, in shock. I’d heard scary stories through the grape-vine, of anarchists going for a hike in the Italian alps, only when they get back to their car, a bunch of police are there smoking cigarettes, doing nothing but letting the anarchists know they’re watching. The Italian police are big on this type of thing, and they also enjoy planting transponders on cars and surveillance bugs in electrical sockets like Soviets. I suddenly remembered all of this, and that Italy had a new far-right Prime Minister, the first woman to hold the job, and then suddenly it hit me. It was October 22, the 100th anniversary of Mussolini’s march on Rome. All of the bickering fascist political factions had magically resolved their differences so that Giorgia Meloni, (ie: Miss Melons) could be sworn in on this very day. This was bad, and someone somewhere thought it was worth keeping an eye on me. I really couldn’t imagine why. I was just going to stay with my friend, and her mother. Wholesome.

Really, I’d lay the blame on Nature as well as Fortune, were I not convinced that Nature is extraordinarily prudent, and that Fortune has a thousand eyes, though fools insist on representing her as blind…so it is with these two rulers of the world, who often conceal their rarest treasures in the obscurity of trades that are deemed the humblest, so that when they are revealed by necessity, their light may gleam the brighter.

-Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron (Sixth Day, Second Story), 1353

The Fifth Story

I lost a couple hours walking around the hill to the next station, but at least I knew no one was following me. I waited until the last minute to buy my ticket, then I waited outside the first train car until the attendant forced me to get aboard. I didn’t think anyone was attached to me, it would be insane to have a cop follow me on a train, but then again, I didn’t have a smartphone, I wrote strange emails, talked to my parents and friends over the landline, and had no public internet presence. In other words, I was sketchy as fuck to a variety of people, so maybe it wasn’t so insane to have me tailed on a train, but why would they do that? I bought my ticket in front of a camera, and they knew exactly where I was going, the Repubblica di Firenze.

Once again, I’d planned to surprise an old friend, only now I was worried. I got off the train at the main station, Santa Maria Novella, even though my friend’s house was near the next station down the line. I figured I could lose any tails in the throng of Firenze’s tourists, who always choke the entrances to the ancient city center. As I plunged through this mess, I noticed many more surveillance cameras than I remembered from my last visit a few years back. Luckily I was wearing a hat and glasses that day, weaving through stone alleys packed with German sightseers and walking like a coke-freak on the way to the bathroom. I lost whoever could have been possibly following me, and by then I was out of the tourist vortex and in the normal city, la citta normale, or at least getting closer to it.

I always know how to find my friend’s family apartmentfrom a nearby brutalist, Soviet-Catholic looking bell-tower, given it stands out in this old-ass metropolis. While everything else is hundreds of years old, this bell-tower was finished in 1962, the brain-child of two architects, one of whom designed the nearby football stadium where the FC is largely anti-fascist. Their cement clock-tower was standing there, looking hella Soviet, when the fucking Arno River burst over the stone embankments in 1966 and rose almost 7 meters (20 feet), devastating this stone city built in the narrowest spot of the river valley. No tourists ever come see this Cathalo-brutalist masterwork, visible across the eastern half of the city, and for me it was the beacon to my friend, whose mother had been one of the angeli del fango, the mud angels who saved precious books and artwork from the great flood of 1966.

Like any decent person, I thought I’d arrive with groceries, but before I walked inside the COOP, I saw something weird on the corner. Two young men dressed in collared shirts were trying to hand out fliers alongside a sloppily dressed old man, who didn’t look as happy as the youngsters. They were in front of UPIM, a sort of up-end department chain, and I sat nearby so I could watch them through their reflection in the store window. It didn’t take long to realize they were fascists, and then I remembered it was the 100th anniversary of Mussolini’s march on Rome. This wasn’t so great, but I didn’t know what to do, so I walked across the street towards the COOP (no, not co-op), only before I could enter, I saw two police step out of their blue car. For a split second, I truly thought I was going to Italian jail, but then they just stood there watching the fascists, back-up in case anything happened.

When I came back outside with two bags of groceries, the cop cars had multiplied and now there were several standing on the corner, guarding the fascists against hecklers. Free speech in the EU, I guess, but I hope that paints a clear picture of October 22, 2022, as it happened on that street corner in Firenze. Apparently, the fascists were also marching in Rome and a lot of other places, but I didn’t know that, I was just a weirdo with a backpack and two bags of groceries, so I left that whole mess and walked almost up to the train tracks, but not quite. As I’d hoped, the lock on her building door had failed to click shut, as was often the case, and I walked straight up to her family apartment where I found my friend and her mother busy making dinner. They were both overjoyed to see me, they made a scene about the groceries and then told me to take a shower, which I did, because I smelled horrible, as usual. After that, we feasted and got drunk until no one could keep their eyes open.

I ate an Italian breakfast that morning, some toast, some sugar biscuits, coffee, an orange, and it took forever, given neither my friend or her mother had anything they needed to do. The tourists still hadn’t left, the days were still warm, and for the next days, I remembered why Italy can be so charming, at least if you can ignore the fascists. We cooked almost every night, except when I insisted on buying them dinner at any place they wanted to show me, in which case I ate delicious Tuscan food made with fucking organic produce grown within a days drive. It was mushroom season when I arrived, so we ate a lot of those, and everything was really good for us, at least until my friend and I finally went on a long walk along the train tracks, smoking a big spliff and really catching up on all the sketchy stuff. I’d just finished telling her about my Ukrainian friends and why I left when we reached the tunnel, the one that changed our topic of conversation.

To get from one side of the tracks to the the other, there’s a large underground pedestrian tunnel covered in graffiti, a beautiful people’s gallery of free art, and in the middle of this tunnel was graffiti for Alfredo Cospito, demanding his freedom and condemning his isolation regime. This silenced us, a reminder that anarchists in Firenze were getting active, some of them. We walked mutely down the tunnel, past graffiti which commanded us to BURN THE GALLERY, and finally came to a pedestrian ramp back up to the street.

On the wall before the ramp, both of us paused to admire a whole wall dedicated to an infamous poster, known in both Firenze and Iași. In fact, the creator of this work was a Moldovan like myself, raised in Iași, and this image of a woman wearing a high black collar is now famous in both cities. The woman just stares in both images, but in Romania there’s a phrase below her neck reading how long do you resist? In Italy, the image has no text, making it apolitical and leaving her intense gaze up to the viewer’s imagination. I guess we decided right there to do something, anything, however minimal, because unless we made ourselves seen, our struggles would fade beneath the lapping tide of war propaganda, endlessly telling us that Kherson would soon be liberated, that the war was almost over.

I can’t say we really did anything at first, not wanting to draw the attention of the Italian police, but the juices were definitely flowing. The days were still warm, although the nights were getting chilly, and I learned that energy costs are actually pretty fucking insane in Italy. My friend in Paris never brought up the cost of heating her massive family apartment, given she’s wealthy, but here in Firenze, my friend and her mom refused to turn on the radiator, hoping to get through October without jacking up their bill. It was something like three times the normal price, electricity too, and as I came to learn, many people in Italy wanted both Russia and Ukraine to agree to a ceasefire, on the left and the right, fascist as well as communist.

A big peace march was planned in Rome by the left, something which was also supported by Catholics and the trade unions. This was set for November 5, but I had no intention of going south. Instead, my friend and I were going north to an illegal Halloween warehouse party in Modena, a place we’d be able to meet up with old anarchist friends and see how they felt about the struggle ahead. Unfortunately, the state also had plans to be there, only we didn’t know that as we rode the train north on that fateful Saturday night. Let’s just say I had a really good time and didn’t fall asleep until past dawn on Sunday, waking up in a tent with a bunch of old friends, Euro-trash Gen-X scum-fucks just like me, all there for the illegal warehouse party, something popular when we were young. We ate together when we woke up, mostly talking about Alfredo Cospito and his hunger strike, and from what everyone said, it was clear the movement to support him was growing, both on the streets and in the prisons.

There is a man named Juan Sorroche Fernandez who is currently in prison in Terni, sentenced to 28 years for a bomb attempt against the Lega Nord, the fascist party which Matteo Salvini belonged to. At the time of the attack, August 2018, that creep Salvini was in power, both as Deputy Prime Minister and Interior Minister, allowing him to enact his version of fascism on the little people. Juan was caught in Brescia in May of 2019, allowing the pigs to parade him around as a captured terrorist and keep building their classical narrative of the evil anarchist bomb-thrower, given Juan was quite prolific, if I can use that word. He had now joined Alfredo Cospito in the hunger strike, as of October 25, 2022, and I only learned this that night from my friends, not from the internet, which I didn’t feel safe checking in Italy, not really, not yet.

I learned a lot as we ate food and got hydrated, preparing for another night of dancing, and much to my surprise, another anarchist had also joined the hunger strike, an anarchist named Ivan Alocco who was charged with torching six cars in Paris, including one for an embassy. The guy has a twelve year-old daughter and was being stalked and surveilled by the French secret police before his arrest. Once he was behind bars, the piece of shit flic tried to interrogate his daughter. I didn’t know any of this, but that night I learned he’d joined Alfredo’s hunger strike, despite not having been sentenced yet, unlike the others. He was in what the French called détention préventive, meaning he had to sit there until the fools in robes had sorted enough documents and harassed enough children.

We were all about to go dancing again when I ate a giant handful of magic mushrooms, given that I never take ecstasy, which apparently everyone was on. I’d made sure to eat up before taking them, but these must have been mushrooms from heaven because I dissociated for large periods of time, lost in some sort of waking dream that involved me dancing, but when I became lucid enough to try and find some friends, reality came crashing back in. Apparently the Interior Minister had ordered our little party to be evicted, something people found out on the internet, and in my mushroom haze, I wandered out of the warehouse, through the tents, and saw the police massing down the road, their blue lights strobing just to unnerve drugged out morons like myself, and it worked, to be honest. For much longer than a split second, I thought they had come just for me, and only me.

It’s still not really clear what went down, but I somehow convinced my friend that we needed to sneak out of the party through the fields, like partisans, and somehow this transformed into both of us walking through the night across the countryside. We were already on the edge of Modena, our minds swirling from adrenaline and psychedelics, and we somehow managed to follow the freeway southeast, though not so close any cars would see us. My friend and I hardly talked for hours, lost in this rural darkness of Emilia-Romagna. We passed through one sleepy stone town after another, never encountering a soul, and even had to cross a river, the Panaro, one of the Po River’s tributaries. We had jackets, our bags, and that’s it, just an intoxicated urge to keep walking through the country.

It was just before noon when we reached Bologna, which is around 40 kilometers from Modena, let me assure you. Mushrooms are a hell of a fungus, allowing us to walk for around 10 hours and think it was actually a big adventure, which it was. Towards the end, when dawn got us all excited, I began reciting all the stories from The Decameron that took place in Bologna, the ancient city just over the horizon. One involved an old man, a renowned physician named Master Alberto, and he convinced some kind Bolognian woman that the older part of the leek, the head, is less disagreeable and perhaps a little pleasanter to the taste than the rest of it. It’s true, we marveled, stumbling forward: all the flavor is at the bottom of the leek, the oldest part, old like us Euro-trash Gen-X scum-fucks.

As we got closer to the city, I kept on narrating The Decameron, badly remembering the story of Beatrice de Galluzzi, who deceives her husband and takes a young lover under his nose. She even tricks her lover, forcing him to lay beside her husband in the bedroom, but in the end the lover is allowed to scold and beat the husband (who’s also his boss btw) while retaining his position in the palace as hired man. If I could have only remembered these lines as Bologna finally came into view: O singular sweetness of Bologna’s fair ones! How worthy of praise you have always been in matters of the heart! You were never fond of tears and sighs, but ever lent a willing ear to lover’ suits, and yielded yourself up to amorous desires! If only I had the eloquence to praise you, my voice would never weary!

We stopped in the first cafe we reached, somewhere on the outskirts of the city. It felt like we moved in, like I spent a lifetime in the bathroom, and we gorged on pastries, downed 1000 espressos, and asked for lots of shitty tasting tap-water. The magic mushrooms had completely vanished, along with all that nice adrenaline, so the water tasted really bad. I was back in reality, but not completely, not yet. I had to look up at the TV before I fully comprehended what had happened. On the screen were images of the party being broken up, of people being arrested, of endless police surrounding a warehouse at the edge of Modena. And then, in the same broadcast, I saw what the fascists had been up to while I danced like an imbecile with a bunch of freaks.

Turned out that a bunch of fascist losers gathered in the hometown of Benito Mussolini, a place south of Bologna called Predappio. 2,000 fascists got to give their salutes and wave their flags and voice their support for the new fascist Prime Minister, who is literally called Miss Melons (ie: Signora Meloni) if translated into English. Meanwhile, our little party was now being depicted on television as a national disgrace, with Meloni promising to crack down on this plague upon Italia. My friend and I were now officially coming down, our brains depleted of those meager chemicals which keep us insufficiently happy on good days. In this state of abject depression, we hoofed it to the train station and rode back to peaceful Firenze where a warm bed was waiting for us.

It gives me the utmost satisfaction to see how a clever man can be led by the nose by a mere woman, like a ram taken by the horns to the slaughterhouse. Though I can’t really give you credit for being clever, as you haven’t had an ounce of brains in your head from the moment you let the devil of jealousy enter your heart.

-Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron, 1353

The Sixth Story

Both of us were deeply affected by the raid on our party, which if I haven’t mentioned was called Witchtek, and we mostly sat around for the next week, numbed by the news. Along with around 4,000 other partiers, we were now pawns in an Italian television-drama, one the government hoped to use as propaganda for its true objective: restricting the number of people who can legally assemble on the street. Neither of us could believe a simple rave would lead to such a spectacle, so to distract ourselves, my friend and I took turns reading The Decameron. Her mother even joined us, having loved the book since she was young, but both of them insisted we read it in the original Italian, which was fine by me.

I am now forced to pause for a moment and let you know this Italian language I previously mentioned is actually just the Florentine dialect. You see, for example, people in Roma have their own distinct dialect, though not so distinct as people from Napoli, where the dialect can often sound like a different language. The language that the Italian Republic decided everyone should learn to speak was the dialect of Firenze and nowhere else. It clearly evolved from Latin, like all the others, and it was first given formal expression by a man named Dante Alighieri, who you probably know as Dante, the guy who wrote about hell and stuff.

His Commedia of hell, purgatory, and heaven would later inspire Giovanni Boccaccio, who would go on write The Decameron in Florentine dialect rather than Latin. Two generations younger than Dante, Boccaccio is the one who added the Divina to the Commedia, immortalizing it as the Divine Comedy for all time, just as both of their works helped make the Florentine dialect the official language of Italy. All of this was carefully explained to me by my friend’s mother, in much greater detail, and I have to say, until I met her, I never knew a single person could know so much.

They lived in their family apartment at the top floor of an old building, and thanks to this blessing, they had access to the lone patio. The weather was somehow still warm, the feels of summer still holding tight, and from this magical patio, we could gaze across the red-tiled roofs of ancient Firenze all the way to the graceful hill leading up to Fiesole, a little stone village that once housed Etruscan and Roman settlements. Just below this village, less than a kilometer from the crest of the hill, was the villa and estate where The Decameron is told, where Boccaccio might have stayed during the last days of the Black Plague. While his words were read aloud to me in the original Florentine dialect, it was a real treat to stare at the villa where all of these stories are recited by the kings and queens of the day, each of them crowned with a laurel, the highest honor in Firenze, apparently.

My friend’s mom was cool, she even smoked spliffs with us, and most of those first sunny afternoons of November passed with us laughing at stories written over 600 years before. I guess that’s the main difference between Dante and Boccaccio. Dante just isn’t funny. Boccaccio is. Many of his stories manage to be truly hilarious while also conveying universal truths about our miserable species, but one of them was so haunting you should probably know about it, a story written over a century before Columbus sailed off to commit genocide in exchange for gold coins.

One day, in the church of San Giovanni, where new paintings had recently been installed, a group of local artists were milling about, soaking it all in. One of these artists, Calandrino, starts talking to a gay, young, venturesome spark named Maso del Saggio, who tells him of a place where one can find magical stones. In this utopic Basque country, vines are fastened to the stakes with sausages, and a goose can be had for a penny, with a duckling thrown in for good measure. Calandrino is swept up in this tale of a land where there was a mountain all made up of grated Parmesan cheese, and inhabited by folk who spent all their time making maccaroni and ravioli, which they boiled in capon-broth and then spilled out pell-mell, so that whoever was the nimblest, obtained the largest share. And last but not least, a stream of the most generous vintage flowed close by—the most delicious wine you’d ever hope to taste, with not the tiniest drop of water in it.

This is funny by itself, but even funnier when Calandrino believes it, and he soon learns from Maso del Saggio that there are also magical rocks to be found in Tuscany. One of them, the black heliotrope, could make the bearer invisible. Armed with this misinformation, Calandrino recruits his friends Bruno and Buffalmacco into this get-rich-quick scheme, and together they pick up all the black rocks they can find. I won’t spoil the ending, so let’s just focus on some European dipshits picking common rocks off the road, thinking they’ll become invisible, and rich.

Like I said, this was written before the colonization of the new world, and this magical heliotrope could easily be gold. It was exactly the type of European idiots like Calandrino who sailed off to what they called India and eventually began looking for the magical land of El Dorado, where everything was made of gold. I really doubt Boccaccio knew what he was tapping into, but many of the major themes of colonization are in there: greed, stupidity, delusion, but above all, the assertion that searching for false treasures will inevitably lead to violence against those who exist below these foolish treasure-hunters, be they indigenous people or their own Florentine wives. Really deep stuff, especially given he came from the same city as Amerigo Vespucci, the clown-prince of Firenze who helped the King of Portugal figure out that Brazil was not only not India, but ripe for genocide and exploitation, all in the name of a magical rock called gold.

Pretty heavy, even though it’s wrapped in a funny little story, and it comes with all sorts of other amazing gems, starting with the maccaroni and ravioli. By the year 1353, we know from The Decameron that Chinese-inspired pasta had become common enough to receive distinct shapes and names, just as the depiction of a mountain made of grated Parmesan cheese was meant to invoke hunger and longing in the reader. In fact, this culinary utopia, where all the food is free, is strikingly similar to the Big Rock Candy Mountains, an old hobo song from the US, one of the few gems your miserable country ever produced. As far as I know, The Decameron contains the first written iteration of this fantasy land (also known as Paese della Cuccagna, or the Land of Cockaigne) where everything is free, even alcohol. Unfortunately, as I’ve hopefully shown you, magical lands where everything is free can be dangerous fantasies, especially when they’re superimposed on real living populations.

We didn’t finish The Decameron that first week of November, before the rains came, but we did watch the Pasolini movie version, the one from 1971 that’s only got 10 of the 100 stories, but at least it includes one of my faves, the one where Andreuccio spends most of the story covered in shit, though it’s not as funny the book, where I literally couldn’t stop laughing. I’d never seen it before, I never liked Pasolini, even if he is some sort of gay icon, but I liked The Decameron well enough, especially its jolly energy, something the book also has. If only I could have just stayed fixated on The Decameron, but no, not me.

Soon enough, I was finding myself taking walks to the immigrant run internet cafes (yeah, they actually still exist), telling myself I just wanted to keep up on the news (just a little news, man), but twenty euros later, I’d realize I just spent hours reading social media. At first I was fixated on Kherson, the whole reason I’d fled my anarchist commune, and it appeared that this historic liberation was proceeding rapidly, with the Russian army announcing it would withdraw its troops from Kherson city on November 9, 2022.

Actually, the entire army was withdrawing from its positions north of the Dnieper River, and by November 10 the grand old Ukrainian army was rolling in, hoisting blue and yellow flags, giving the occasional sieg heil, and by November 11, a truly loaded day, the Ukrainians were in full control of the surrendered territory. All the propaganda was victory this and victory that, with major news agencies comparing it to D-Day in WWII, which made me fume, because that wasn’t close to being true, it was just some bullshit Zelensky thought up after a bump of coke.

In reality, the Russian army had literally stripped everything out of the city, stolen everything remotely useful, and damaged everything that was definitely useful, even taking the zoo animals. All the flag waiving and heartfelt videos were masking over the simple fact that the city would be uninhabitable amid the swiftly approaching winter. No one cared about this, not when they could dunk on the loser Russians already firing shells from the other side of the river, and all of these explosions were hidden under endless celebrations, as if something truly tremendous had taken place that would change everything. I would have gone coo-coo if there hadn’t been some positive developments in the struggle to free Alfredo Cospito from solitary confinement.

On November 7, 2022, an anarchist prisoner named Anna Beniamino joined Alfredo’s hunger strike. She was locked up for being part of the Informal Anarchist Federation and exploding a bunch of bombs, like a good Italian anarchist, and one of these attacks was alleged to have been done with Alfredo Cospito, and for this she was sentenced to 17 years in a Roman dungeon. In the days leading up to her joining the hunger strike, some vegan anarchists torched several slaughterhouse meat-trucks in Athens, claiming solidarity with Alfredo and Giannis Michaelidis, the famed Archer of Syntagma, imprisoned once again after escaping and going on the run, a truly a remarkable personal achievement. Way to bring the fire, vegans! After that, people kicked it up a notch.

On November 5, someone torched a cell-phone tower way in the mountains of Trentino, which is almost into the deep Alps. They left some graffiti on the tower, signaling it was done for Alfredo Cospito, and that same day some comrades torched multiple prison contractor trucks in Bologna. The next day, November 6, anarchists sabotaged the train lines in Rome, leading to multiple delays on the national system in defense of Alfredo Cospito. The very next day, Anna Beniamino joined Alfredo, Ivan, and Juan in their hunger strike. It seemed like everything was coming together in the anarchist world, especially after the Germans went wild and torched some prison contractor trucks in Leipzig and Berlin, all for Alfredo and the hunger strikers. After that, anarchists in Milano went crazy on a bunch of banks in their cold northern city, then after that, more action in Torino, another northern snow-globe type city.

Meanwhile, the Ukrainians were going on a propaganda blitzkrieg, along with the US and the EU, hyping everyone up with the liberation of Kherson. I knew something bad was coming any day now, something really bad, and it seemed like Italy was going to be there for it. Unlike her fascist buddies who got her elected, Miss Melons was gung-ho about continuing military aid to Ukraine, and she made this quite clear in the days after her election. Thing were made even weirder after the big peace march in Rome on November 5, when all the big Italian left factions marched alongside unionists, Catholics, and the 5-Star Movement through the streets of the ancient city, tens of thousands of them, all calling for an end to military aid for Ukraine. At the same time, the Italian fascists were also calling for an end to military aid to Ukraine, so yeah, weird.

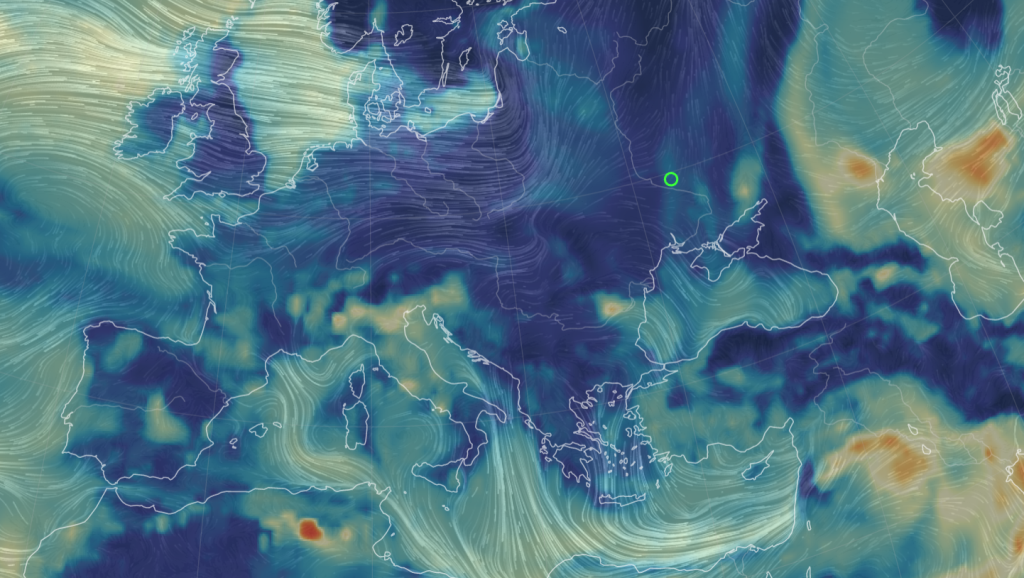

I was in the internet cafe reading about all of this, obsessed at the time with Miss Melons’ conflicts with orange-faced Silvio Berlusconi, trying to figure out if she was playing her own game, when I suddenly felt someone step behind me, but just to the side. When I turned around, I saw my old friend Werther, who I’ve written about before. He was wearing a hat and sunglasses and was clearly coming to the internet cafe for the same reasons as me, maybe even for something sketchier, but in that moment, all we could do was laugh, though I should have known better. It was the early evening of November 15, 2022, and for some reason, Werther was wearing an $80 black sweatshirt from a Scottish hooligan outfitter with a name that begins with a Z. It was just a coincidence, that prominent Z, but as we saw each other, over 80 rockets were heading запад, or Zapad, or West, fired from Russia and soon to cripple Ukraine’s already ravaged infrastructure.

It’s true Buffalmacco and I live as gayly as you see—more so, in fact, though if we depended on our art, or the income of any of our bits of property, we wouldn’t even be able to afford the water we use. But I don’t want you to think for a moment that we go breaking into people’s houses. We simply go bush-ranging, and without doing anybody harm, we take whatever we like or need. That explains why we live as merrily as you see, without a care in the world!

-Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron (Eighth Day, Ninth Story), 1353

The Seventh Story

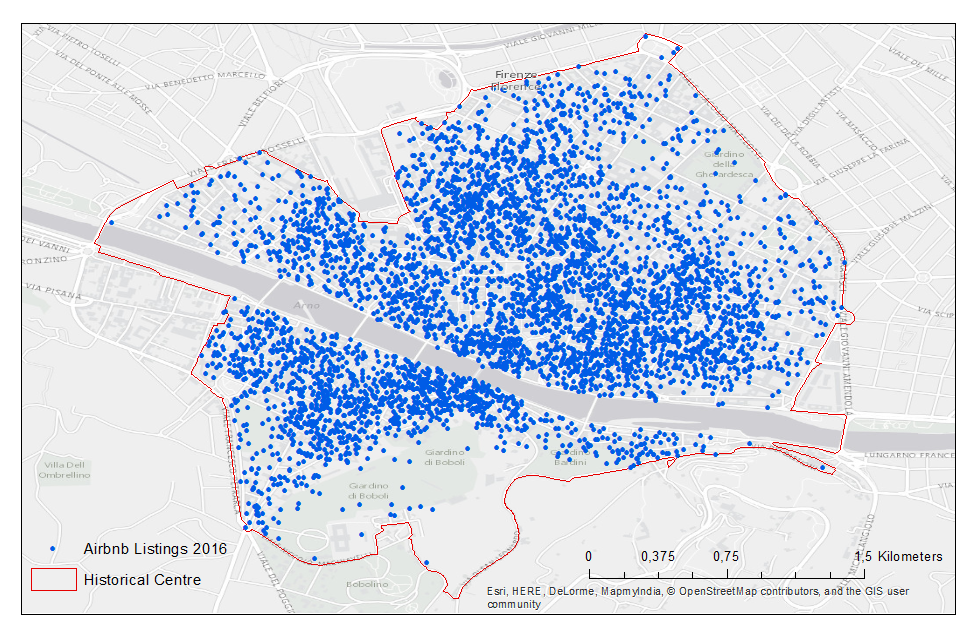

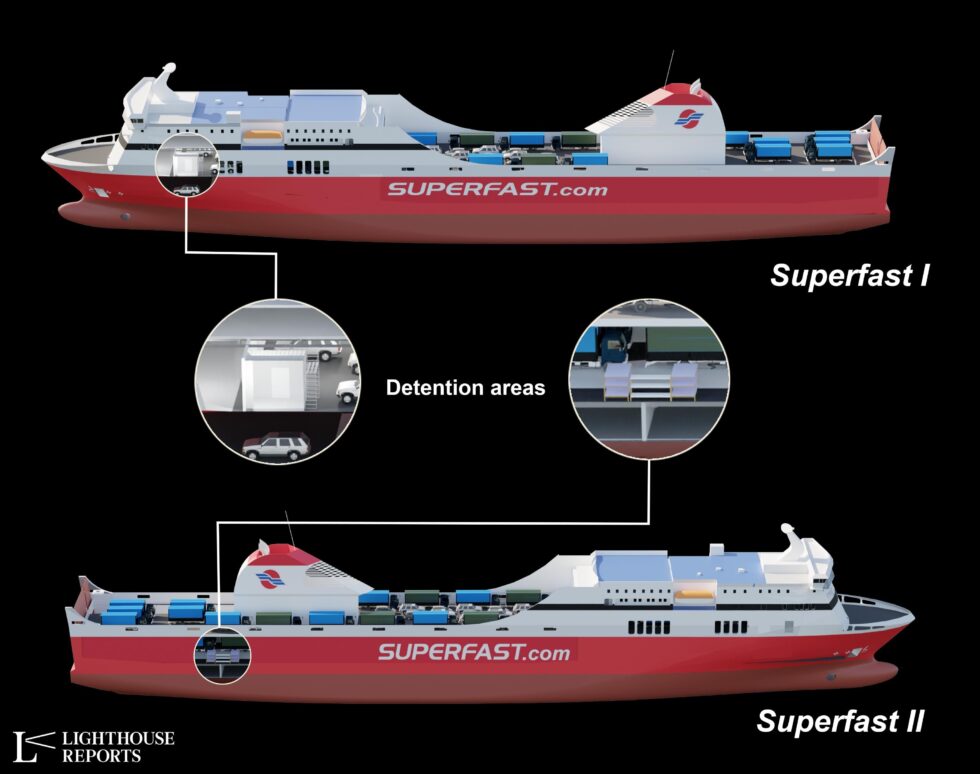

Neither myself nor Werther could have imagined WWIII almost began that night, but as we walked from the internet cafe towards where he was staying, Russian missiles were falling towards their targets, some of them being intercepted by Ukrainian air defenses. Werther led me to a minor but well known piazza near the city center just as two Russian-made Ukrainian air-defense rockets misfired westward across the Polish border and landed in the village of Przewodów, killing two peasants. I didn’t know this happened until we entered one of the old stone buildings and walked through a labyrinth of some sort, up a flight of backward-tilting stone stairs, through another labyrinth, and into some hidden building across a courtyard. When I asked where we were going, Werther said this whole building was an AirBNB owned by what was called a super-host.

I didn’t have time to vent my furious, near-homicidal anger because he opened the apartment door to a kitchen full of frantic people, all of them in their underwear. One of them was hunched over a computer, narrating the recent turn of events in Poland, and I stood there numb as I learned that elements of the Polish state and Zelensky himself were boldly asserting that this was a direct Russian attack on Poland, a NATO member, and thus Article 5 needed to be initiated. In other words, a pan-European ground war, otherwise known as WWIII. I stood there numb there for a while, unconsciously undressing just like Werther, and we waited there for a while as the news came flooding in. It was only when NATO chimed in, announcing they were still gathering information, that I finally asked why the heat was up so high. Not only was the heat up to the max, all the windows were open, even though it was raining.

Werther explained that he and several friends had rented multiple AirBNB units around the piazza and were constantly running the heat to ensure their super-hosts definitively lost money during this energy crisis. According to young Werther’s strange theory, AirBNB prices had dropped across Firenze with the onset of the rainy season, what with all the tourists being gone, so this was the prime time to strike. It was all starting to make some sense, especially when I gathered it was costing each of these people around €25 a night to make the super-hosts lose over €100 a night, and they’d already been camped in the piazza for a week, the heaters running non-stop. I fell in love with Werther all over again, and in my underwear, I sat with him and his Swedish friends around the computer as Zelensky revealed to the world that he was perfectly willing to initiate a nuclear holocaust.

Luckily that didn’t happen, but that night was the closest we’ve all come to total fallout apocalypse in Europe, and it wouldn’t be until later that the fucking CIA and Pentagon stepped in to shut down their rabid dog Zelensky, passing themselves off as the voice of reason by asserting it was in fact Ukrainian rockets that killed those two Polish peasants. In a single night, all of the hollow victory propaganda surrounding the liberation of Kherson vanished, replaced by mass electrical blackouts across Ukraine. From east to west, the Russian army had finally done what it refused to do last winter, and now they were crippling the vital energy infrastructure one salvo at a time, in preparation for something during the deep white-walker cold that waited beyond the solstice.

Before I went home that night, Werther showed me all the other AirBNBs his weird Euro-friends had taken over. Half of them were chilling under the loggia, a sort of colonnaded, free-standing stone structure of a dozen arches and a roof, a place to get out of the rain, and all these pseudo-squatters were smoking spliffs with the immigrant dudes, most of them Arabs with a few Kurds thrown in. We all got real high while Werther pointed out the ten AirBNBs they’d rented. Half of them were now filled with guys off the street who needed to get dry and take a nap, and given these buildings were owned by super-hosts, there was no one there police the entrance. In fact, the super-hosts were just real-estate companies based in countries outside of Italy, and I doubt even the Italian state gave two-shits about this scheme of Werther’s, what with AirBNB being headquartered in San Francisco and owned by a literal US man-baby.

Werther and I weaved through the rain-soaked city after that, finally able to soak in the pure medieval vibes now that the streets were empty and all the cobblestones covered in puddles. He told me he’d been floating around post-COVID Europe, somehow ending up in Sweden where he stayed in a cabin and finished one of his writing projects. Now he was here with these Swedish freaks, and all the money to float their AirBNB scheme was coming from guilty Swedish libs who found this strategy a healthy compromise. I’d never heard of anything like it. Aside from costing these super-hosts thousands of euros in energy, they were also mapping every detail of the buildings, information which they would then anonymously give to some Florentine anarchists also interesting in tanking AirBNB. Only some fucking Swedes would get behind something like this, and as Werther made me remember, it was also the fucking Swedes who funded African anti-colonial liberation movements and made Black Panther documentaries back in the 1960s.

Werther and I got a drink in a small bar off Viale Giovanni Amendola, a giant six lane road that’s the closest thing central Firenze has to a freeway. It has different names as it wraps around the old city, and we watched its endless traffic flow through the rain. I still couldn’t believe I organically ran into my old friend from the US, but there he was, and before he could slip away, I wrote down an intersection on a piece of paper and told him to meet me there at noon tomorrow, that I wanted to introduce him to my friend. He promised me he’d be there, and after our drinks and cigarettes, we parted ways and I went back to my worried friend, who was half-convinced the Italian police finally got sick of me and sent me back to Romania. Not the case, fortunately, and that night we stayed up drinking with her mom as I explained where I’d just been, a modern tale as weird as any in The Decameron. Needless to say, WWIII didn’t happen that day, nor the next.

My friend and I met up with Werther the following afternoon and went to a nice place for lunch. His Italian was horrible, so we talked mostly in English, and somehow our conversation meandered to Alfredo Cospito and his hunger strike, as well as the sudden flush of anarchist actions in solidarity with his struggle. We all agreed this was what the anarchist movement needed to get going in Europe after the COVID lockdowns, but we hated that Alfredo and the others were sacrificing their health and potentially their lives, and the only thing which made it half-tolerable was that it was their choice. They wanted us to be so angry that we would act. That was the point. The waiter kept asking if we wanted food but our appetites were pretty much gone, so we paid for our bottle of wine and then took a little walk towards the city center.

On the way, we admired some of the street art, with Werther showing us the remaining posters that bore the image of a woman in a high black collar, put there by a Romanian hipster from Iași. A lot of them had been taken down, no new ones had gone up during COVID, and as Werther accurately observed, seconded by my friend, the lockdown had put a damper on Firenze’s usually vibrant street art, with only one major artist consistently putting their pieces up across town, even in the industrial suburbs along the river. This artist was fond of matchsticks that stand as people do, in various stages of combustion, and we saw these figures along our path. Aside from that, there wasn’t a whole lot, so the three of us vowed to print and put up a new poster, one that would be overtly anarchist.

As we had this thought, we came upon a lone piece of street art, one that resonated deeply, especially given our recent attempt at lunch. It was the black and white image of a woman sipping an aperol sprtiz, the iced orange-colored drink beloved by international tourists, but inside the glass was the flour-de-lis symbol of Firenze, implying the city was being sucked dry. Around this image was the unambiguous phrase CITTA MORTA, or DEAD CITY. While the vibes were certainly accurate, my friend actually got angry, claimed some fucking hipsters had made it, and wanted to prove that her city wasn’t dead. To do this, she dragged us up some soggy stone streets to a tripe stand. Yeah, a fucking tripe stand.

Being a backwoods-ass Moldovan peasant, I was familiar with eating tripe and knew it was never a dish of the upper classes. I think my friend wanted to gross out Werther and test his resolve, not knowing he and I once consumed countless bowls of tripe-filled menudo in Oakland taquerias. Regardless, we sat down around this food-cart and ate lampredotto, the lowest part of the cow stomach. It was cooked in a nice broth, smothered in salsa verde (that’s right, Italians have salsa) and then served on a panino, like a sandwich. It was delicious, and everyone sitting around us was dressed in their color-coded worker’s uniforms, trash-men, construction workers, all the like. This was truly the people’s food, and I gave my friend a big stinky garlic kiss in thanks. Werther just ate in silence. Then he ordered a second.

When I consider why we are here—chiefly, I believe, to amuse ourselves and have a good time—I think that anything that tends to give us occasion for mirth and joy has both its due time and place.

-Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron (Ninth Day, Fifth Story), 1353

The Eighth Story

Werther got obsessed with the tripe sandwiches after that, so I met him at the same stand every day, one near his piazza, or plaza, and when we took our sandwiches to eat beneath its loggia, we were surrounded by not only his Swedish friends, but all the immigrant guys they’d befriended, as well as some Florentines who’d figured out that Werther and the other freaks had essentially seized the entire piazza. I came back at night sometimes and got to talk more with these Florentines, who all drank at the one bar that stayed open late, and as the AirBNB conspiracy continued to burn through hundreds of euros in wasted energy, they drank here every night, spreading that guilty Swedish money as widely as possible. One night, this Florentine lady said her family used to live in one of the AirBNB buildings, and that very night, she was sleeping in her old bedroom.