From The Transmetropolitan Review

The Flight of Fulvia Ferrari from Perenelle Flamel on Vimeo.

Fulvia Ferrari was the daughter of a San Francisco anarchist named Enrico Travaglio, although few ever knew this to be true. After her mother Isabelle disappeared in Russia, Fulvia went searching for her in the 1930s only to end up imprisoned in a German concentration camp. Once the US Army liberated the survivors, Fulvia returned to San Francisco under a false name and tried to reclaim the lost worlds of the anarchist Latin Quarter and insurgent Telegraph Hill. When she’d finally achieved some of these goals, Fulvia decided to meet with her father, although she never called him that, preferring to use his first name: Enrico.

Fulvia was born in 1915 and grew up in a Mendocino County commune just north of San Francisco. She moved to San Francisco in the early 1930s and it was here that she first met her father. After returning from Seattle in the 1920s with his third wife Esther, Enrico settled in the bayside town of Sausalito before moving back to his beloved San Francisco. According to the oral histories compiled by Paul Avrich in his Anarchist Voices, Enrico was “fiercely anti-Bolshevik after the Russian Revolution and broke with some of his friends who became Communists.” While he was still living in Sausalito, Enrico would “meet Eric Morton on the San Francisco Ferry,” although according to his wife Leah, “they never talked about anything important.”

Eric Morton was no ordinary anarchist, and just like Enrico Travaglio, he was also a sailor. When Alexander Berkman was imprisoned for his assassination attempt against Henry Clay Frick, it was Eric Morton who attempted to a dig a tunnel to rescue him. Eric Morton helped Emma Goldman smuggle dynamite and arms into Russia between 1905 and 1907, edited The Blast newspaper with Alexander Berkman, and remained in San Francisco to fight the local Italian fascists during the rise of Mussolini. According to Emma Goldman in her 1931 autobiography, Eric Morton was “a man of intelligence, daring, and will-power.” When he would meet with Enrico Travaglio on the San Francisco Ferry in the 1920s, the Russian Revolution now a decade past, these two men were certainly discussing the future. A few years later, when Enrico had moved back to San Francisco, his secret daughter appeared at the front door, looking for her mother Isabelle.

The 1920s and 1930s were a violent time in the former Latin Quarter of San Francisco, now known as North Beach. As fascists took over the Italian state, their local supporters became more aggressive on the streets, triggering bloody clashes over the next decade. Between 1926 and 1927, the local Catholic Church was hit with four bomb blasts, a campaign that targeted the church for its support of Mussolini. During the fifth attempted blast, two anarchists were shot by police before they could light the bomb and one of them soon died from his wounds.

In 1927, two Italian anarchists were transporting a bomb through the Richmond District of San Francisco when it suddenly went off. Rather than blow up the Italian Consulate as planned, Angelo Luca lost a leg while his comrade was instantly killed. Despite receiving a permanent wound, Angelo denied any knowledge of the bomb and was never charged with a crime. A decade earlier in 1917, he’d married a painter named Jessey Dorr, one of the first graduates from the all-woman Mill’s College in Oakland. Just before she married an insurrectionary anarcho-communist, Jessey had burnt all of her canvases and swore to never paint again, an event that signaled her shift away from the bohemian world (although a few of her paintings survived). She lived with Angelo in a house in the Mission District at 650 Capp Street and raised their two children, one of whom became an art and sculpture lecturer at UC Berkeley. For the rest of his life, the family of Angelo Luca would remain close friends with Enrico Travaglio.

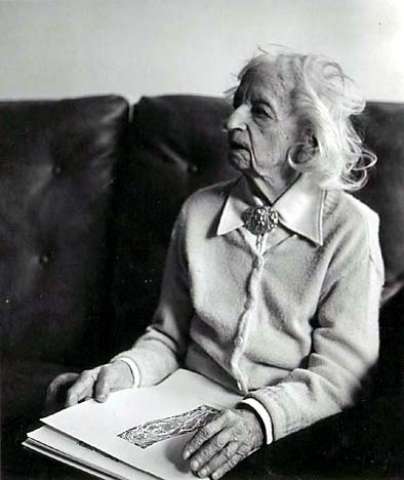

Jessey Dorr, 1970s, with her painting “Off to the Oyster Beds”

In the middle of classical fascism’s rise, the massive 1934 Waterfront Strike took place in San Francisco, a violent labor conflict that left nine people dead, including Fulvia’s three uncles. While this effort led to a General Strike and the creation of the ILWU union, it also caused a wave of repression against the perceived Communists who’d infiltrated the labor movement. Using modern machine guns and federal soldiers, the bosses subdued the strike just as Hitler was throwing anarchists and communists into concentration camps. In this horrible time period, Fulvia decided to leave San Francisco to find her lost mother, the last surviving member of her family besides Enrico, who she hardly knew.

When she returned in 1947, having lived through Stalin’s USSR and the Nazi’s concentration camps, Fulvia immediately reclaimed her family’s lost waterfront territory. After she was secure in her new San Francisco life, Fulvia met with her father in 1951 and began a relationship that would span the rest of Enrico’s life. While never revealing who she was to Enrico’s wife, Fulvia met with her father on a regular basis, hoping to rebuild the anarchist world he’d lost. In the process, she read Enrico’s elusive history of anarchism in the United States, learned the secrets that led up to her birth, and discovered her father was born in Milano, just like her maternal grandfather Antonio.

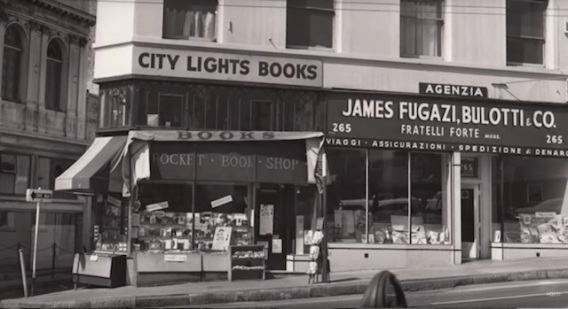

During the late 1940s, the nephew of IWW leader Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and the son of Carlo Tresca moved to San Francisco and began working as a sociology teacher. In 1953, he opened City Lights Bookstore with Lawrence Ferlinghetti before returning to New York a few years later. The bookstore is still there on the corner of Broadway and Columbus, the former gathering spot where fascists had once listened to Mussolini’s radio broadcasts. During the late 1950s, it would become a major center of the beat movement and publish books that mentioned the Wobblies, anarchism, and the gone world of their parents generation. Fulvia Ferrari was often there.

In 1956, during one of their meetings, Enrico asked Fulvia to visit his old hometown and do what she could to help the anarchist movement. Starting that year, Fulvia began a series of trips to Northern Italy that culminated with her involvement in the Torino Fiat Strike and the Piazza Statuo Riots of 1962. It’s this period in Fulvia’s life, between 1956 and 1962, that we’ve documented in our short film The Flight of Fulvia Ferrari. While posing as an art dealer, Fulvia’s trips across the ocean helped divert money into the anarchist movement and breathed new life into the global struggle. With her lover, she also smuggled weapons onto the Cape Verde Islands and Guinea Bissau from the late 1950s to the early 1960s, helping the anti-colonial rebels begin their uprising against the Portuguese. Despite her efforts, Moscow eventually stepped in to replace their operation. This pattern would only repeat itself.

Fulvia returned from Torino in 1963 and remained in San Francisco until the late 1970s, a moment when she was forced to permanently leave her beloved coastline. In 1968, she’d sat in front of the television with Enrico and watched as the Parisian riots of May filled the screen, a spectacle that brought great joy to her old father. With militant struggles breaking out across the planet, Enrico Travaglio died happy in July of 1968. His friend Angelo Luca would pass away four years later in 1972, followed by his wife Jessey in 1977. By then, most of the old-school anarchists had moved south to Los Gatos where they had “picnics from time to time to raise money for the Italian and English anarchist press.” Years after Fulvia vanished from the San Francisco Bay Area, these anarchists continued to reside in Los Gatos, with many of their children still living in the region. The last of these elders who gave their oral histories to Paul Avrich died in 1993. Most of them were born in the 19th century. Today, their final refuge of Los Gatos is the home of Netflix corporate headquarters.

While we were completing this third installment of our series on Fulvia Ferrari, the actress who stood-in for Fulvia passed away from natural causes. Valentina Cortese, born in Milano in 1923, became a movie actress during the fascist dictatorship and starred in her first role in 1940 at the age of seventeen. Her first two films were made at Cinecittà studios, a film-production company established by Benito Mussolini that carried the slogan: Cinema is the most powerful weapon. The studios were bombed in 1943, the same year over one thousand Jews were taken from Rome to Auschwitz. Like many other artists, writers, directors, communists, and anarchists who lived in Italy through these events, Valentina didn’t do very much to fight against the dictatorship during the 1940s, and most spent the rest of their lives trying to redeem themselves. Once the war was over, Cinecittà became a refuge camp for two years before returning to film production. Since then, the studio has tried to forget its origins.

After the end of WWII, Valentina signed a contract with 20th Century Fox and began filming movies with US directors. Her first role during in this time period was in the 1949 noir-film Thieves Highway, filmed almost entirely in San Francisco. It’s a massively subversive film with the notion of “free-enterprise” heavily critiqued. It depicts a Greek sailor just returned from WWII who’s instantly exploited by the market and turns to a waterfront sex-worker for help. Valentina knew exactly what kind of film she was making and was allowed the freedom to deliver her best performance. The director was Jules Dassin, a former Communist who’d renounced his affiliations with the Party when Stalin made a non-aggression pact with Hitler. Despite his hatred for state communism, Dassin was soon put on the Hollywood Blacklist and completely shut out from the US film industry.

Unlike him, Valentina Cortese continued to make movies for Hollywood but was never given the full-on star treatment or elevated to the heights of her Anglo-Saxon peers. According to an interview Valentina gave in 2012, “I could have remained in Hollywood for who knows how long, but I never made compromises. Never was in a producer’s bed.” Because of her refusal to sleep with an unnamed director, Valentina’s career was destroyed. She remained independent her whole life, acting in a Brecht play and an Antonioni film, and she died last week in Rome on July 10, 2019. May she rest in peace, and may these images from her films bring you closer to a better world.

Long live Fulvia Ferrari! Long live Valentina Cortese!

There are 2 Comments

just so you know, Thieves

just so you know, Thieves Highways is available for free on youtube

jules dassin’s the shit. no

jules dassin’s the shit. no one be afraid of diving back into old films. there are some real subversive gems from way back (like pre-code and noir eras). there was even a well regarded anarchist filmmaker, jean vigo, although i have yet to see this person’s films.